After Wade Hampton’s election as South Carolina’s governor in 1876, the Red Shirts had fulfilled their primary mission. They were also active during the Hampton’s 1878 reelection campaign, but not to the same level and the group seemed to dissolve. After several decades of silence, the Red Shirts again came to the attention of many in 1908 when the first of four annual reunions were held in South Carolina. The first two were held in Anderson County. These were large gatherings, and were largely propaganda to change the view of the Red Shirts from that of a violent and racist organization to something more benign that would only use violence when necessary. They might have succeeded too, had it not been for a speech delivered by Benjamin Tillman at 1909 reunion.

By the end of the 19th century, the South Carolina Democratic Party had completely adopted white supremacy as its standard policy. In the words of John C. Watkins, Sr., the acting party chairman in Anderson County, printed in the Anderson Intelligencer, October 16, 1890:

“…we hereby call every Democrat in the County, who is willing to help save his race and protect the helpless women and children from Negro domination to meet in mass-meeting at Anderson Courthouse…Don again the red shirts, the emblem of white supremacy; “Old Reformer” is ready to again raise his voice for liberty. Let the state, the world, if necessary, see and understand that the white people in Anderson County are true to their principles of Democracy and the supremacy of the white race…let every Democrat vote, and vote the regular ticket. In doing so you are not voting for men, but for the regular Democracy and white supremacy.”

“Old Reformer” is a cannon that was bought to the upstate during the War of 1812. It is believed to have been brought to Charleston by German emigrants in 1764. The cannon made its way to Anderson in the 1850’s, and it was used fired at important occasions such as Hampton’s campaign announcement and the announcement of his win. For decades it was visible at the courthouse, but today, it is housed at the Anderson County Museum.

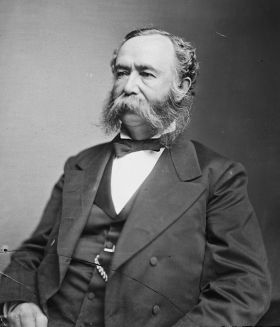

Augustus J. Sitton (www.findagrave.com)

The Red Shirts were introduced in Anderson by Augustus J. Sitton during Hampton’s campaign. Sitton was the quartermaster of his regiment during the Civil War. He was unable to bear arms due to a wound he received at First Manassas so he served in clerical and administrative roles. According to Ellison Capers, Sitton was a member of Hampton’s staff, “and was the originator of the red shirt as a campaign uniform, which was an important factor in ridding South Carolina of the carpet-bag and Negro government in 1876.”

The association between the Red Shirts and their racial past was something that many wanted to change. In fact, there were Freedmen who were members of the Red Shirts. In 1900, a former slave named James Minor of Williamston died at his home at the age of 75. His obituary states that he “took an active part in the red shirt campaign of 1876” and often gave speeches extolling the white man as the best friend of his race. His funeral was attended by a large number of whites and blacks.

The First Reunion

A Maid of the Foot-Hills by J.W. Danial

There was a renewed interest in the Red Shirts in Anderson County during the early 1900’s primarily because of one man and two books. The man was Jesse C. Stribling. He was the first lieutenant of the Pendleton Red Shirt Company. He was a supporter of Hampton in 1876 and after the election devoted himself to his farm and local politics.

The two books were John Reynold’s Reconstruction in South Carolina and a novel by J.W. Daniel, A Maid of the Foot-Hills, set in Anderson County. Both books were published in 1905. Reynolds was a noted author and the library for the state Supreme Court His Reconstruction began as a series of articles printed in The State. They were collected in book form in 1905 and trace a chronological history of Reconstruction, ending with Hampton. Daniel’s Maid was a fictionalized account of Reconstruction with Anderson legend Manse Jolly serving as the inspiration of his hero. Daniel portrayed the Red Shirts in a very sympathetic light, much like the Klan received in the film The Birth of a Nation.

Stribling had a keen interest in the region’s past, and he wanted to remind people of what the Red Shirts had accomplished. Like many of his day, the white supremacy of the Red Shirts was not a negative thing, and it had led to a South Carolina that was prosperous, settled, and without racial violence. To accomplish this, he began planning a reunion, using the annual Confederate veteran reunions as his model. Invitations were mailed to other chapters in the state asking them to gather together to recall their glory days. On August 14, 1908, the first Red Shirt Reunion in South Carolina was held in Anderson County where they had been originally been organized, Pendleton, SC.

Stribling’s intention for the reunion was to educate the current generations on the accomplishments of the Red Shirt and to pass on their beliefs of white supremacy. A parade was held that was reserved for Red Shirt members and their sons. Local Pendleton boys organized themselves into a junior Red Shirt company and were responsible for dragging the Peacemaker cannon through the streets in the parade. One speaker encouraged the boys to “learn of the trials their fathers endured and the struggles they made to insure white supremacy for their children.”

For Stribling and the other former Red Shirts, there was a distinction between their work and that of the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan used violence to solve all problems and acted outside the law under the cover of darkness with their faces covered. The Red Shirts operated in the open, and would use violence only as a last resort, when the circumstances forced them. This was the message of the first reunion.

The Second Reunion

The first Red Shirt Reunion in Pendleton was such a great success, that plans were made for another reunion the following year. This time it would be moved to Anderson, and it was a much larger and more inclusive event. Held on August 25, 1909, the second Red Shirts Reunion began with a lavish parade of approximately 2,000 people, including veterans of the Red Shirts, Spanish-American War veterans, brigades of firefighters, speakers, the Orr Mill Band, and 50 members of the Daughters of the Confederacy. The parade made its way through the center of Anderson’s on Main Street, and ended at University Hill, the site where Hampton made his campaign announcement in 1876.

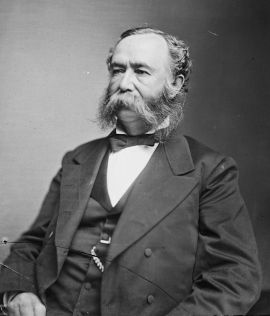

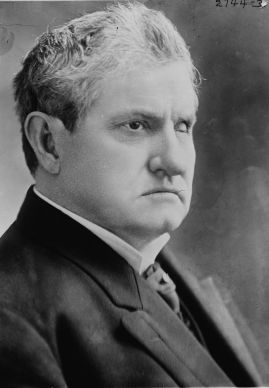

Benjamin R. Tillman (Library of Congress)

The keynote speaker of the 1909 reunion was none other than Benjamin R. “Pitchfork” Tillman, an early member and ardent supporter of the Red Shirts. Tillman had backed Hampton as a Red Shirt, but be became disillusioned with Hampton soon after the election. This division eventually led to a split with the state Democratic Party eventually split and Tillman became the leader of his own faction called the Tillmanites. A popular politician across the state, he was elected governor of South Carolina (1891-1894) and U.S. Senator (1895-1918).

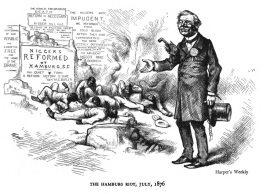

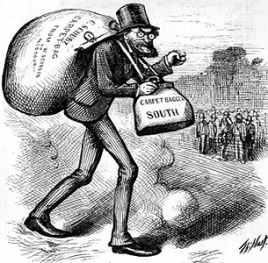

Tillman’s speech in Anderson was entitled “The Struggles of 1876: How South Carolina was Delivered from Carpet Bagger and Negro Rule,” and it destroyed forever the façade of Red Shirt restraint and non-violence that had been fostered in the first reunion. Tillman was known for speaking in overly racial terms and would proudly proclaim himself a white supremacist when given an opportunity. He used the second Red Shirt reunion as an opportunity to discuss perhaps the most infamous of the Red Shirt actions: the Hamburg Massacre.

Covered in a previous post, the Hamburg Massacre was a pivotal moment in race relations in South Carolina. Over 90 men were indicted in the deaths in the massacre, including Tillman, but none were ever tried for their crimes. The bulk of Tillman’s speech consisted of a detailed account and defense of the massacre, and he relates the events with a cold matter-of-fact manner that does not hide his racism and support for white supremacy. None of this was surprising. Tillman was known for bragging in public speeches and on the Senate floor about the violence he had perpetrated against blacks in his early days.

To the thousands standing before him in Anderson, Tillman delivered a long speech that runs over 30 printed pages. These were among his words:

“The purpose of our visit to Hamburg was to strike terror, and the next morning (Sunday) when the Negroes who had fled to the swamp returned to the town (some of them never did return, but kept on going) the ghastly sight which met their gaze of seven dead Negroes lying stiff and stark, certainly had its effect…

“It was now after midnight, and the moon high in the heavens looked down peacefully on the deserted town and dead Negroes, whose lives had been offered up as a sacrifice to the fanatical teachings and fiendish hate of those who sought to substitute the rule of the African for that of the Caucasian in South Carolina.

“We have in truth waved the bloody shirt in the face of the Yankee bull and dared him to do his worse. It is needless to say that this daring act on the part of the whites served to intensify the fears of the Negroes, while among the whites the bond of race drew us closer together.”

The Red Shirts simply could not escape their racial past from this speech. Although there were a few more reunions interest in the group disappeared by 1911, and they ceased to gather together, gradually swept into the proverbial dustbin of history.

Legacy

The key figures in the Hampton campaign all continued their political careers past the turbulent events of 1876.

Daniel Henry Chamberlain, the last of the Reconstruction Governors, returned to New York and practiced law. He was a constitutional law professor at Cornell University from 1883 to 1897. After retiring, he traveled extensively in Europe before moving to Charlottesville, Virginia, where he died in 1907. He was buried at Pine Grove Cemetery in West Brookfield, Massachusetts. His tombstone makes no mention of his term as Governor of South Carolina, but he is called a “scholar, patriot, soldier, lover, jurist, and statesman.”

Wade Hampton III was elected to a second term as governor in November 1878, but he resigned February 26, 1879, after being elected by the state Senate to the United States Senate. Hampton was not a candidate for the position and he did not want it, but he took the seat and remained in the U.S. Senate until 1891. Hampton was appointed by President Grover Cleveland as United States Railroad Commissioner in 1893, and remained in the post until 1897 with he retired from public life. Hampton died in 1902, and was buried at Trinity Episcopal Church in Columbia, SC.

Martin Witherspoon Gary’s Tombstone (Old Tabernacle Cemetery, author’s collection)

Martin Witherspoon Gary commanded the Red Shirts in their implementation of the Mississippi Plan. He made his headquarters at Oakley Park in Edgefield. Today, the house is the property of the Town of Edgefield and the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and is the home of The Red Shirt Shrine and Museum. Gary was elected to the state Senate in 1876 where he served two terms. His was a long time ally and supporter of Hampton, going back to the Civil War, but that ended when Hampton failed to appoint him to the U.S. Senate in 1877 and 1879. Gary retired from politics in 1881, and died at his home in Cokesbury, South Carolina, later that year. He was buried at the old Tabernacle Cemetery near Cokesbury.

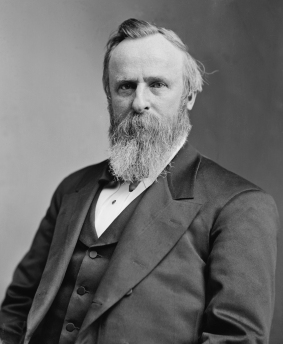

Rutherford B. Hayes served for two terms as President of the United States from 1877 to 1881. He declined to run for a third term and retired. During his administration, Hayes promoted civil service reforms, attempted to reconcile the differences in the nation that remained after Reconstruction, and believed in a government that was color blind. Despite being the man who ended Reconstruction, Hayes is often regard as among the best of the worst presidents in United States history. He died at his Ohio home in 1893, and was buried on Oakwood Cemetery in Freemont, Ohio.

Benjamin Ryan Tillman, the firebrand speaker, white supremacist, Red Shirt leader, friend of the farmer, and education advocate, was elected governor of South Carolina in 1890 and he served two two-year terms. During his four years as governor, 18 blacks were lynched in the state, and the South Carolina Constitution of 1895 was drafted which disenfranchised most of the voting blacks in the state. He was instrumental in the growth of Clemson and Winthrop. Tillman was elected by the state Senate to the United States Senate in 1895, as proscribed by the United States Constitution. He would hold his seat until his death in 1918. Tillman was buried at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Trenton, SC. His tombstone includes the following inscription: “He was the friend of leader of the common people. He taught them their political power and made possible for the education of their sons and daughters.”

Both Hampton and Tillman have been honored at locations across South Carolina. Each had a monumental statue on the statehouse grounds. Because of his backing of the higher education, buildings at Clemson and Winthrop bear Tillman’s name. To honor the “Savior of South Carolina,” a new county was carved out of the northern part of Beaufort County by the General Assembly in 1877. Governor Hampton signed the bill on February 18. 1878, naming it Hampton County.

The lives of Hampton, Tillman, Chamberlain, and the others involved in the campaign of 1876 ended decades ago. The Red Shirts no longer exist, and although their are groups motivated by hate and racism, the idea of white supremacy as a legitimate political idea is no longer accepted as mainstream. Justified or not, the legacy of the 1876 election and the men who fought it remains with South Carolina over 140 years later.