Part one of the series on the Whitner family covered the life of Joseph Whitner, the founder of the family. Orphaned at an early age and alone on the streets of Charleston, South Carolina, Joseph Whitner educated himself, led troops during the American Revolution, and amassed a fortune in the Pendleton District. Politically, Joseph Whitner was an anti-federalist, fearing a strong, centralized federal government and believed that the states were best at governing themselves. These beliefs were passed on to his three sons, Benjamin Franklin, John, and Joseph Newton. Of these, it is Joseph Newton Whitner, Sr., who bears the title “Father of Anderson.”

Joseph Newton Whitner, Sr., was born April 11, 1799, near Pendleton. He was the youngest son and fourth child of Joseph and Elizabeth Whitner. He attended school in Union, South Carolina, and there are tales of his run-ins with the law. In one incident, Whitner was visited by the deputy sheriff on some relatively minor matter. Unbeknownst to the deputy, Whitner carried a pistol to school. When the deputy tried to arrest Whitner, he pulled out his pistol and told the officer that he would not go willingly. Whitner was joking, according to his own later recollection, but the deputy did not take it so and shots were nearly fired when the deputy got off his horse.

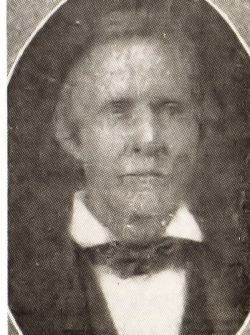

Joseph Newton Whitner (Anderson County Museum)

After finishing his schooling in Union, Whitner graduated from South Carolina College in 1818, and despite his earlier misbehavior, learned the law by reading it. He returned to the Pendleton District where he built a successful legal practice in just a few years. Whitner took an interest in politics and served in the South Carolina House and Senate from the 1820’s to 1835, representing his home district.

He is most remembered legislatively for authoring a plan to divide the Pendleton District. Before even Pendleton District was created, the land had been used by the tribes of the Lower Cherokee as hunting ground. There were no permanent settlements in what is today Anderson County, Cherokee or otherwise, until after the Revolutionary War. The land had been ceded to the State of South Carolina in 1777 by a treaty with the Cherokee, but the war prevented any real settlement policy from being developed and employed. Soon after the war ended, however, Revolutionary War veterans bought up tracts of land in the region, many for a very cheap price and the upstate was soon divided into districts for government. Each district had a courthouse town which was the center of local government.

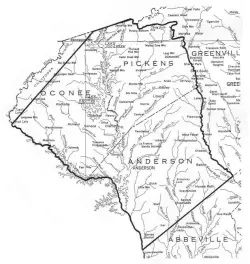

Map Showing Outline of the Original Pendleton District and the Subsequent County Divisions. Although shown on the map, Oconee County was not created until 1868.

The area of South Carolina west of Greenville and north of Abbeville Counties was named the Pendleton District (and the Washington District for a short period of time) from 1790 to 1826. The courthouse was located at Pendleton. The district covered nearly two thousand square miles, and with the growth in settlements had become nearly ungovernable. Its courthouse was far from many of its key towns, and new settlers were continually moving in.

As a young representative, Whitner had an idea. He proposed breaking up the district into two smaller, more manageable units. In his legislation, Whitner proposed naming the units after two local heroes of the Revolutionary War: Generals Robert Anderson and Andrew Pickens. Anderson and Pickens Counties were created by an act of the General Assembly on December 20, 1826.

The former courthouse town of Pendleton was not abandoned, however. A new courthouse, called Anderson, was established near the center of the new county. A small frame courthouse was built, businesses began began to establish themselves around the county square, taverns and inns opened, a gridwork of streets were laid, and lots were for sale.

During the late 1820’s, Whitner married Elizabeth Hampton Harrison, the daughter of James Harrison, Jr., and Sarah Earle, a granddaughter of Elias Earle, U.S. Congressman and one of the earliest settlers of Greenville County. Between 1830 and 1845, Joseph and Elizabeth had nine children, all born in Anderson.

- Joseph Newton Whitner, Jr., born November 14, 1830, died July 13, 1882. C.S.A. Wounded at First Manassas. Married Amelia Mellvina Howard and had issue.

- Sarah Frances Whitner, born March 21, 1832, died January 24, 1924. Unmarried.

- Elizabeth Teccoa Whitner, born March 1833, died July 8, 1906, in Warm Springs, Virginia. She married Col. Thomas Jamison Glover, Sr., who died on August 31, 1862, from his wounds at Second Manassas. Emmala Reed recorded in her diary that Mrs. Glover was forced to play the piano for the “entertainment” of Union troops during Anderson’s occupation after the war.

- James H. Whitner, born November 3, 1833, died May 2, 1886, in Greenville, South Carolina. C.S.A. Died unmarried of heart disease.

- Benjamin Franklin Whitner, born February 22, 1835, died January 14, 1919. Married Anna Pleasant Church, December 21, 1858, and had children five children, including William Church Whitner, the man who brought electricity to Anderson.

-

Monument Dedicated to Elias, Rebecca and Samuel Whitner, erected by their siblings at First Presbyterian Church (author’s collection)

William Henry Whitner, born November 10, 1836, died February 16, 1872. C.S.A. Married twice but no children. Served on the staffs of Gen. Roger A. Pryor, Gen. Micah Jenkins, and Gen. Bushrod Johnson. Later moved to Madison, Florida, where he died.

- Dr. Elias Eugene Whitner, born November 22, 1839, died March 21, 1872. Died unmarried of caused unknown, the second Whitner child to die in 1872. He had just recently moved his practice to Greenville and bought a home.

- Rebecca E. Whitner, born November 1, 1843, died May 29, 1845. Rebecca died just a few weeks after the Anderson fire.

- Samuel Earle Whitner, born April 26, 1845, died September 29, 1845. Samuel was the second child of the Whitners to die in 1845.

Shortly after his marriage, Whitner and his wife moved from Pendleton to Anderson. He purchased a house from William Moses Chamblee, Sr., two miles west of downtown. The house over looked a wide creek to the east. Elizabeth covered the grounds with roses and the home was known as Rose Hill. According to a nearby historical marker, the house was built around 1794. Whitner lived at Rose Hill for the remainder of his life, and he dedicated much of his years to the development of the town he had founded.

On April 6, 1831, Whitner presided over a dinner of Pendleton’s leading men that was held to congratulate Vice President John C. Calhoun on his “clear and conclusive vindication.” There had been a split politically between Calhoun and President Andrew Jackson over the growing power of the federal government. Less than two months later, Calhoun gave his famous Fort Mill Address in which he laid out his legal and moral defenses for the Theory of Nullification, which argued that states could nullify acts of Congress that they deemed out of line with the Constitution. Whitner was a strong Calhoun supporter and believed him when Calhoun said,

“The States…formed the compact, acting as Sovereign and independent communities. The General Government is but its creature; and though, in reality, a government, with all the rights and authority which belong to any other government, within the orbit of its powers, it is, nevertheless, a government emanating from a compact between sovereigns…”

Whitner resigned from his state Senate seat in 1835, after being elected Solicitor of the Western District of South Carolina, a position he held until January 26, 1850, when he was elected a law judge, serving until his death. Whitner was opposed to drinking strong liquor, and as solicitor, he often gave temperance speeches and lectures at district courthouses in his circuit. His demeanor on the bench was less confrontational and he was considered “a lawyer’s dream come true.” As a judge, Whitner was conscientious, patient, kind, and courteous to the attorneys appearing before him.

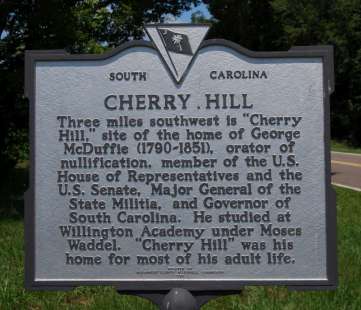

He was named a lifetime trustee of South Carolina College in 1837. Others appointed that year included future governors Wade Hampton III and George McDuffie, and James Louis Pettigru, famous for his statement upon the state’s secession in 1860, “South Carolina is too small for a republic and too large for an insane asylum.”

First Presbyterian Church, Anderson, South Carolina (author’s collection)

Although his father had been born a Lutheran, the Whitners converted to Presbyterianism after they settled in Pendleton. Joseph Whitner had been a major contributor to the Old Stone Church and his son would also be a founding force for another congregation. Whitner donated a large tract of land in 1837 to the local Presbyterian community for use as a church. Anderson Presbyterian Church, now known as First Presbyterian, was organized September 23, 1837.

There were thirteen charter members of the church, including Whitner and his family. Whitner remained a member of the church his entire life. The first frame structure was completed in 1839 and it was in this building that Whitner worshiped. Adjacent to the church was the city’s first public cemetery, although the property belonged to the church, the final resting place of many of the early Whitners. Anderson’s first Sunday School was organized at First Presbyterian in 1855. A historical marker was erected at the church site in 1968 by the board of deacons.

Joseph Newton Whitner

The year 1845 was a difficult year for the Whitner family. Whitner maintained an office at the Benson House, a large hotel in downtown Anderson, in which he stored his personal records, library, and papers. A fire swept through the western side of Anderson in April 1845, destroying many of the wooden buildings. Whitner was able to save his library and papers, but the office was not so lucky. Whitner also owned a large building, previously called Archer’s Hotel. It too was totally destroyed by the fire. The fire destroyed all of the early history of the town. The newspaper office, which stored many of the records was burned to the ground. Within a few months of the fire, Whitner lost his youngest two children, Rebecca and Samuel, just months apart.

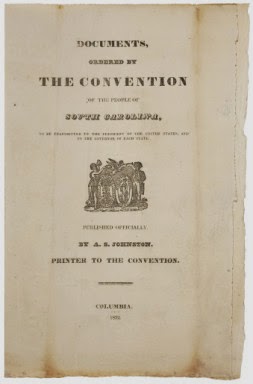

Whitner had adopted many of his father’s political beliefs but he took them a step further. He was a zealous advocate of the States’ Rights Doctrine, and the Theories of Nullification and Secession, and a life-long supporter of John C. Calhoun. As such, Whitner was often a delegate to several like-minded conventions such as the Southern Cooperative Rights Convention in Nashville, Tennessee, June 3, 1850; the 1852 Southern Rights Convention; and the South Carolina Secession Convention, December 1860. It was at the state’s convention where he signed the secession ordinance as one of five delegates representing Anderson County.

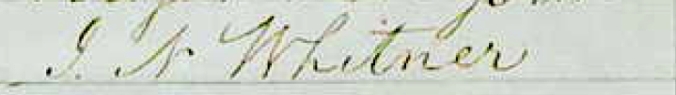

Joseph Whitner’s Signature on the South Carolina Secession Ordinance

Whitner was a slave owner. According to the 1850 federal Slave Census, he owned nearly eight slaves. They ranged in ages fifty five to less than a year. Their names are not recorded in the census but based on the ages given there appeared to be several family groups.

It was during this decade that Whitner turned his attention south for a business venture. Like many other members of his family, the prospect of developing land in Florida was too much to avoid. Whitner purchased ninety acres in Leon, Florida, for development. Although the investment paid off, Whitner later remarked that he would have made more had been there to over see the operation, adding “you can’t run a plantation from afar.”

By 1860, Whitner was a very wealthy man. According to the census for that year, he real estate was valued at $30,000 and his personal estate at $150,000. In today’s dollars, his real estate would be worth nearly one million and his personal estate over four million. His wealth, however, could not help Whitner fight on the battlefield for his cause. He was simply too for active service during the Civil War. His five surviving sons, however, all served in the Confederate Army.

Joseph Newton Whitner Tombstone (find-a-grave)

Joseph Newton Whitner died on March 31, 1864, and was buried at First Presbyterian. He is remembered in Anderson by a street and a creek that bear his name. These intersect near his home. Rose Hill remained in the Whitner family for several years before being purchased by William W. Humphreys. It was later a country club and museum. Sadly, Rose Hill has not survived. It was town down in the 1960’s.

Anderson, the town that Whitner founded was destined for greater things. It would emerge from the Civil War and Reconstruction, and see a period of economic growth during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It would fall to his grandson, William Church Whitner, to light the way.