The final part in the series on the Orr family will cover the lives of James Lawrence Jr. and Dr. Samuel Marshall Orr, both giants in their respective fields. The two men were the first sons born to James and Mary Orr and they left a lasting mark on Anderson in the form of a textile mill.

James Lawrence Orr, Jr.

James Lawrence Orr, Jr. (August 29, 1852-February 26, 1905) Named after his father, James Lawrence Orr, Jr. was the eldest son of the James and Mary Orr. He was born in Abbeville at the home of his grandfather, Dr. Samuel Marshall, August 29, 1852. His maternal uncle was Col. Jehu Foster Marshall, hero of the Mexican War, notable figure of Abbeville, and commander of a Confederate regiment. Col. Marshall died during the Civil War.

Orr was a tall man. He stood six foot six inches, towering over nearly everyone he knew. Most of his contemporaries only reached his shoulder. He was physically very strong, weighing nearly 275 pounds. His strength was not only physical, however. His had a keen mind which marked him for future success.

Orr’s Passport Application, completed in 1873, when his father was minister to Russia. (National Archives)

At the age of twenty, he accompanied his father to Russia where he served as his private secretary. He returned to Anderson in 1873, and on the twelfth of November, married Bettie B. Hammett, daughter of Colonel Henry P. Hammett, a local textile leader. After a few years as an attorney, was elected to the South Carolina House as a representative from Anderson County. He was a young and ambitious politician. Early in his career he became a redeemer under Wade Hampton and was a vocal supporter of Hampton’s campaign to redeem South Carolina from Reconstruction. Orr played a pivotal role in the weeks after Hampton’s election.

Hampton’s election as governor caused a split in the state’s government. The sitting Republican governor, refused to give up his office and the there were two General Assemblies, each supporting their candidate. Each assembly met in a different location and each claimed to be there by the people’s will. It was Orr who led the “attack” on the Republican Assembly, and it was he, with a great show of force, who torn down the locked door they were meeting behind.

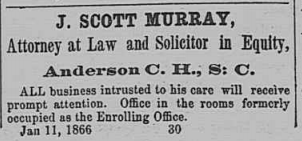

In 1878, Orr was elected solicitor of the Eighth Circuit, and as a prosecutor he had a marked success. Orr was not known for his speaking abilities and, in his own words, would “murder the King’s English” on a regular basis. Orr did not follow any certain grammatical or rhetorical rules, but he spoke with a common sense that was easy for everyone to grasp. It was not uncommon for many young lawyers in the Anderson and Greenville areas to “swear by Lawrence Orr.”

Orr resigned from the solicitor’s office in the early 1880’s and moved to Greenville where he began practicing law under the firm Wells & Orr. This was eventually expanded to Wells, Orr, Ansel & Cothran.

In 1890, Col. Hammett, Orr’s father-in-law died. Hammett was at the time one of the most successful textile pioneers in the state. The industry was still in its infancy and Hammett’s company, Piedmont Manufacturing Company, was in need of leadership. Despite his lack of experience in the business world, the company’s board of directors selected Orr as the next company president. It was here that Orr found his greatest success.

Under his leadership, Piedmont Manufacturing doubled in size and its stock was sold at the highest price for a mill in the state. His success at the mill prompted him to enter politics one more time. This time, however, he was up against the populist force known as Benjamin Tillman. Against his best wishes, he agreed to run on the 1892 gubernatorial ticket for South Carolina as lieutenant governor along with Sheppard for governor. Many of the state’s leading businessmen had begged Orr to run against Tillman himself, but he refused due to the responsibilities placed on him with the mill.

Like Tillman, Orr believed that reform was needed in the state. Unlike Tillman, Orr did not believe in the extreme and racial measures Tillman would take to see it happen. The campaign of 1892 was brutal and speaking engagements often descended into a battle of lung power: whichever side could yell the most. Orr, it was remarked by a contemporary observer, stood out. Despite his lack of speaking skills, his sledge-hammer logic and straight-from-the-hip speaking style actually swayed voters from supporting Tillman, but it wasn’t enough. In the end, Tillman won the election. After this defeat, Orr retired from political life and he dedicated his time to the growth of the Piedmont Company.

Between 1899 and 1900, Orr organized and built a new state-of-the-art mill south of Anderson, the second textile mill in the town, and the first textile mill in South Carolina to use electricity for all its power. Called Orr Mill, it and the surrounding mill village became a fixture of life in the town. Orr was the mill’s first president, John E. Wigington was the first manager, and John Lyons served as mill superintendent until the 1950’s.

Orr Mill, Historic Postcard

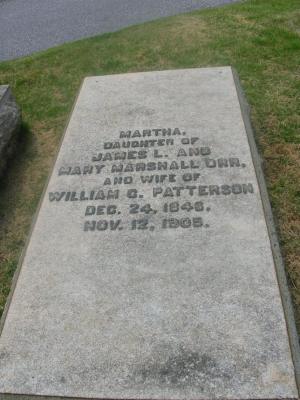

Orr’s leadership of the mill was very successful but sadly shortened by his death on February 26, 1905. Orr died after suffering for a week from erysipelas brought on by a skin infection. He was laid to rest in the churchyard of Christ Church (Episcopal) in Greenville, South Carolina. He was survived by his wife and six children.

Later that year, a cenotaph to James Orr was placed near the Orr Mill on South Main Street where it stood behind a wrought iron fence until 2008 when it was damaged in a storm. The monument was later moved to the Anderson County Museum, and is on display near the entrance. A nearby tablet provides historical context to the monument.

Orr Monument, Anderson County Museum (Author’s collection)

Dr. Samuel Marshall Orr (Anderson Intelligencer, 1896)

Samuel Marshall Orr (June 5, 1855-April 14, 1909) Named after Mary Orr’s father, Dr. Samuel Marshall, Dr. Samuel Marshall Orr was born in Anderson June 5, 1855, the second son of James and Mary Orr. Dr. Orr was reared in Anderson and studied at Professor Ligon’s private school at Anderson, the King’s Mountain Military Academy in Yorkville, and Furman University.

From 1873 to 1876 he gave his attention to mercantile pursuits before beginning to study medicine at Jefferson Medical College in 1877. Orr graduated in 1879, and opened a practice in Anderson as the partner of Dr. Waller Hunn Nardin. Dr. Orr at once found himself in possession of an active practice which has steadily grown until it now extends over a considerable portion of upper South Carolina. He practiced medicine for twenty-five years. His practice was not only successful, it was extensive. He was frequently consulted in medical cases from Abbeville, Greenwood, and Walhalla.

He took a post graduate course in 1892 in New York Polytechnic. He was the president of the Anderson County Medical Society, a member of the American Medical Association, and of the Board of Medical Examiners of South Carolina. He is also first vice president of the South Carolina Medical Association and was formerly lecturer on anatomy and physiology at Patrick Military Institute of Anderson. He is also surgeon of the Blue Ridge and the C. & W.C. railroads.

Dr. Samuel Marshall Orr House (Author’s collection)

He was married in October 1875 to Charlotte Althea Allen daughter of John E Allen of Abbeville County and granddaughter of the late Dr. Charles L Gaillard of Anderson County. They have four children. Ten years later, in 1885, Dr. Orr built a magnificent two-story Greek Revival house at 809 West Market Street. The house was a smaller replica of his father’s home on McDuffie Street, and is an example of a plantation style home in an urban setting. This speaks to Dr. Orr’s stature and leadership role in the community.

As a physician, Dr. Orr grew to care not only about his patients but his community as well. As such, Dr. Orr was very involved in Anderson’s development. He was president of the Anderson Water Light and Power Company, and in this position improved and extended the power system which eventually replaced the old steam powered system the city had been using. He was also the treasurer and director of the Anderson Cotton Mills, vice president of the Anderson Building and Loan Association, vice president of the Farmers and Merchants Bank, and a partner in the Hill-Orr Drug Company of Anderson. After his brother death, Dr. Orr was selected as president of Orr Mill, a position he held until his death. Under his leadership, the mill grew to 57,496 spindles, 1,504 looms, and 600 employees.

Dr. Samuel Marshall Orr Tombstone, Old Silver Brook Cemetery, Anderson, SC (Author’s collection)

Dr. Orr died April 14, 1909, while seeking treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. He was surrounded by members of his family. They had traveled to Baltimore in anticipation of Dr. Orr not recovering. He had been suffering from several illnesses for some time, and they had gotten worse a few weeks before his passing. He was the last surviving son of Governor Orr. His elder brother James had died in 1905; his younger, Christopher, had died in 1888. His sister, Mary Orr Earle, was now the last surviving sibling. Dr. Orr was laid to rest in Anderson’s historic Old Silver Brook Cemetery.